What is energy poverty, and why is it likely to affect women more?

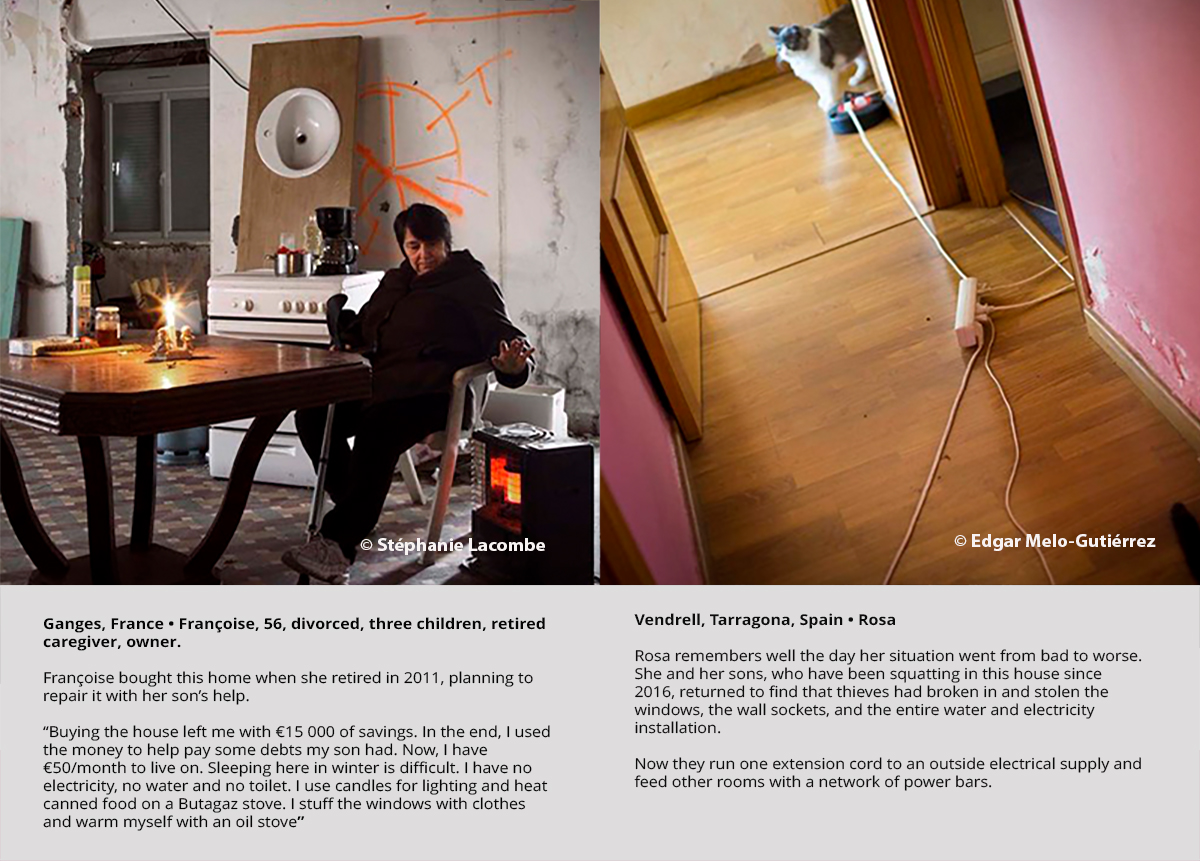

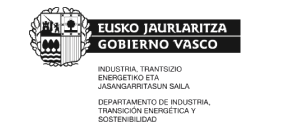

Nadine and Rosa (see photos) are two women who struggle to afford essential energy services to ensure a decent standard of living and health. A person or a household like Nadine's in France or Rosa's in Spain is considered to suffer from energy poverty if they do not have access to the electricity grid, cannot adequately heat their home during the winter or keep it cool during the summer, are unable to sufficiently illuminate it or have the energy to power their appliances at reasonable prices.

Images by Stéphanie Lacombe and Edgar Melo-Gutiérrez for the EXPOSED exhibition of the EnACT project

The European Commission has identified three factors as the main determinants of energy poverty: low income, low household energy efficiency, and high energy prices. In addition, different factors make certain individuals or households more vulnerable to energy poverty, such as age or marital status, the type of household, their health conditions, and among other aspects, their level of energy literacy. In addition, as climate change has increased the volatility of weather, raising temperatures during the warmer months while decreasing them during the colder periods, the probability of vulnerable energy consumers to suffer from energy poverty has increased.

In the case of women and their households, they are more vulnerable to energy poverty since they: (i) have a longer life expectancy than men, and older people are more sensitive to extreme temperatures; (ii) are more sensitive to cold and heat than men for physiological reasons, which increases their risk of energy poverty and deterioration of their physical and mental health; (iii) receive lower incomes and pensions than men; and (iv) have less time for paid work, as they tend to have more responsibility when it comes to household chores and care (Birgi et al., 2021; Energy Poverty Advisory Hub, 2022a).

As energy poverty is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, its measurement is not straightforward; both context (location, climate, housing types, and energy market behaviour) and personal conditions (age, household composition, health conditions, income, etc.) determine who can be classified as lacking basic energy needs. However, the EU Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV) established a set of indicators to measure these household deprivations (Energy Poverty Advisory Hub, 2022b). Two main indicators are the inability to keep home adequately warm (based on personal reports of discomfort with home temperatures in winter) and arrears on utility bills (based on households' reports of their inability to pay their household utility bills on time in the last 12 months).

Did the pandemic and the onset of the current energy crisis affect women more than men?

Now, given the economic crisis that generated the pandemic since 2020 and the energy crisis that began in 2021, it is crucial from the public policy point of view to analyse whether households like Rosa's and Nadine's were more affected than other types of households, and tocalibrate strategies against energy poverty and policies that seek to protect the most vulnerable consumers of gas and electricity.

Using Eurostat data from 2010 to 2021, we find that single-parent households and households with three or more adults are the most vulnerable to energy poverty. Specifically, in the EU, the households with the highest percentage of inability to keep home adequately warm during the winter are those led by women (10% in 2021), followed by those led by men (9% in 2021) or with three or more adults (8% in 2021). Although these percentages have been declining over the last few years, during 2020 and 2021, the percentages increased slightly for all household types, reflecting the effects of the economic crisis and rising electricity and gas prices.

In terms of the percentage of households that are late paying their housing utility bills, households led by women (4% in 2021) are less late paying than households led by men (7% in 2021), indicating a possible higher risk aversion from women (Charness & Gneezy, 2012). The households most susceptible to arrears are those with three or more adults, who are likely to have dependents over the age of 65.

You can click on the ![]() icon to see the interactive graphs in full screen

icon to see the interactive graphs in full screen

In Spain, the percentage of households led by women that failed to heat their homes in winter adequately was higher than those led by men in some years during the analysed period. These percentages remained relatively stable until the Covid-19 crisis in 2020 and the onset of the energy crisis in 2021. From 2020 to 2021, the indicator for female-led households increased by 65%, while for male-led households, it increased by 20%, with women being the most affected by the current energy crisis.

Regarding the indicator for arrears on utility bills, Spain shows the same behaviour as in the EU, where female-led households have fewer arrears than households led by a male adult or households with three or more adults. However, of the four types of households analysed, female-led households experienced the highest growth in this indicator in 2020.

Comparing the behaviour of the indicators for female-led households in Spain with the EU, we find that the percentage of households that cannot adequately heat their homes is almost always lower than the European average, except in 2020 and 2021. In fact, in Spain, between 2019 and 2021, this indicator increased from 9% to 20%, while for the EU, it remained around 10%. Moreover, if we compare this indicator with the data from other countries such as Germany, France, Italy, and Portugal, Spain was only surpassed by Portugal. If we analyse the behaviour of households led by women who are late in paying bills, we also find a similar pattern: Spain presents the lowest levels compared to the EU average until 2019, and between 2020 and 2021, it has the highest percentage of the five countries analysed.

You can click on the ![]() icon to see the interactive graphs in full screen

icon to see the interactive graphs in full screen

In conclusion, women have physiological, health, economic, and social risk factors that make them more prone to energy poverty. When we assess the data for Spain, and the EU, female-led households are slightly more likely to be unable to adequately heat their homes during the winter than male-led households, but those led by women are more compliant in paying their bills. Additionally, the Covid-19 crisis and the onset of the energy crisis in 2021 affected single-parent households led by women more than men, and women in Spain were more affected than most women in the other EU countries.

This higher impact of energy poverty in Spain during 2021 may be due to the higher increase in retail electricity prices in the country during the current energy crisis, which grew by 46% this year, while the EU increment was 17% (see figures until 2022 and the evolution of retail prices and their components in this visualisation). Thus, the proper design, establishment, and implementation of measures to protect the most vulnerable electricity and gas consumers, such as women, is of utmost importance. In addition, as Ihobe and Emakunde mention, tackling energy poverty, while advancing in the energy transition and mitigating the effects of climate change, requires a gender approach, where women participate and lead decision-making in generation projects, such as those of energy communities, or in the design of public policies.

Stephanía Mosquera López

Stephanía works as a researcher in Orkestra's Energy and Environment Lab since November 2022. She is an economist, with a Master’s in Applied Economics and a PhD in Engineering (Emphasis in Industrial Engineering) from Universidad del Valle, Colombia.

Her research focuses on energy markets, especially electricity and natural gas price modelling, market risk measurement and management, and the impact of climate variables.