In the current context, energy concerns seem to have taken hold in public opinion and culture. Fortunately. We have already commented in this blog that the war in Ukraine had settled the debate on the energy and geopolitics binomial, which at first may seem distant to the public, but which in reality is a determining factor in people's daily lives.

Now, as 2023 begins, the next Goya Awards ceremony suggests that the energy issue is playing an increasingly important role in the collective imagination. This year, it is a coincidence that two of the films with the most nominations revolve around an apparent dilemma: the choice between the development of renewable energies and the preservation of the rural environment.

The film Alcarràs (Carla Simón, 2022) takes place in the town of the same name in Catalonia, where the Solé family is resisting the installation of a solar energy park on the land where they have been growing peaches for decades. Meanwhile, The Beasts (Rodrigo Sorogoyen, 2022) contrasts two visions of rural life when the inhabitants of a Galician village are divided over the sale of land for the construction of a wind farm.

Coincidentally or not, and although renewable energies are not central to the scripts, Simón and Sorogoyen's proposals address a growing but historic debate inherent to sustainable development: reconciling social and economic progress with the protection of natural and cultural heritage.

Moreover, the question becomes paradoxical if we incorporate the challenge of decarbonising the economy at a fast enough pace to mitigate the effects of climate change. That is, starting from the premise of protecting natural and cultural capital, are the measures taken robust enough to address the greatest environmental challenge in human history or, on the contrary, can we engage in "overprotection" with counterproductive effects? Given this dilemma, part of the critics are right to point out one of the most powerful images in The Beasts as a quixotic metaphor in which the protagonist, small and full of doubts, contemplates an imposing uncertainty in the form of a windmill.

The main debate is not really about whether to decarbonise or not. The discussion is about what alternatives or models are available and, in particular, who benefits from the measures adopted. Thus, concepts such as just transition, rural depopulation, visual pollution, NIMBY (not in my backyard), degrowth, energy colonialism or extractivism, among others, are emerging in public opinion and academic discussion. These are different approaches or critical visions on energy transition that are intertwined in a broader and more global discussion, not only on the deployment of energy sources, but also integrating the procurement of resources (such as critical minerals for energy transition), the development of infrastructures or mobility. These perspectives suggest that social support for the energy transition is not homogeneous and may be conditioned by a variety of factors. Their reflection in popular culture, such as in the aforementioned films, indicates that the debate is alive and may complicate the decarbonisation of the economy.

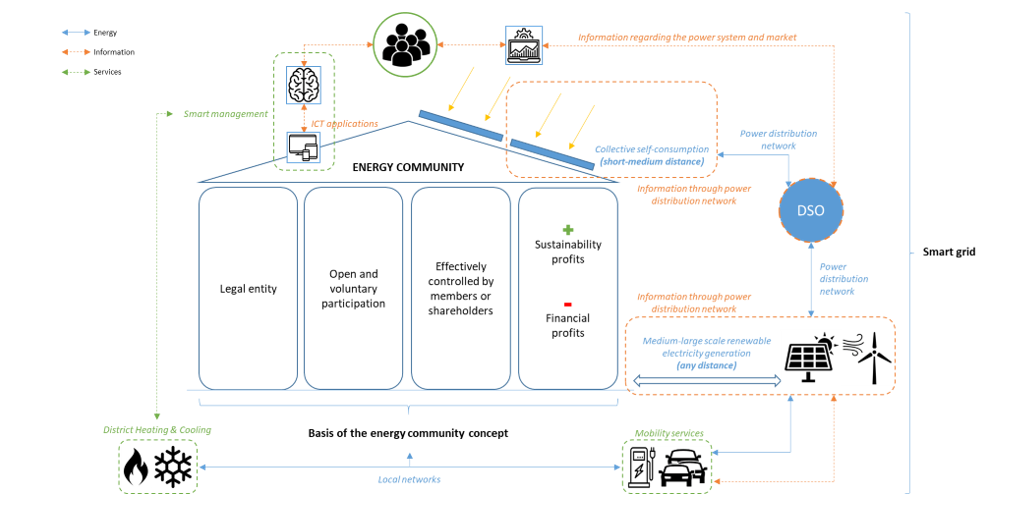

Motivated (in part) by this potential gap between society and the energy transition, the European Union has been promoting the figure of energy communities since 2018. These are new ways of organising energy activities (generation, storage, consumption, etc.) aimed at supporting the transformation of traditional energy systems into new systems characterised by the penetration of renewable energies, a progressive decentralisation of energy resources, a leading and active role for consumers and a set of innovative activities related to energy management, among others.

One of the most notable points of energy communities, as defined by European legislation, is that they specifically prioritise environmental, economic or social benefits for citizens and/or the local areas where they operate, thus avoiding prioritising financial profitability (which does not imply that they are incompatible). Some examples could be the reduction of electricity bills, the fight against energy poverty or support for institutions that carry out social work (schools, associations, etc.). With this foundational approach, energy communities aim to act as a link between society and the energy transition and to strengthen the support and active involvement of citizens in the development of renewable energies.

Given the growing interest in this concept, a few months ago Orkestra published a study on case studies of energy communities, analysing eight projects set up in Spain (four of them in the Basque Country) and another eight in other European countries. This is an area that has been evolving rapidly since its publication, as demonstrated by the recent extension of the geographical limit of collective self consumption.

The following figure from the report shows a simplified conceptualisation of the main points that define energy communities (4 pillars) and some characteristics of interest. It should be noted that they:

1) present high potential for innovation (digitalisation, aggregation of demand, bringing flexibility to the system, etc.), both technological and social;

2) they constitute a new horizon for the smart grid;

3) and enable the integration of different forms of energy (e.g. biogas, hydrogen) and sectors (e.g. mobility).

One of the main conclusions is that there is a wide and increasing range of energy community models, many with a clear application in the rural environment and in small towns. Given that these entities seek to involve citizens in the deployment of renewable energy and generate benefits for them, perhaps an energy community would have helped to drive the debate in Alcarràs or The Beasts.

But then again, only maybe. Keep in mind that energy communities are not magic formulas, any more than anything else is in the challenge of mitigating climate change. We are talking about providing options to improve the balance between sustainable development and urgent decarbonisation. But environmental challenges are built on another set of complex socio-economic and demographic challenges. This is crudely shown in one of the dialogues in The Beasts between Antoine (Denis Ménochet) and Xan (Luis Zahera), when one defends the enjoyment of a simple life in the village (his "home") and the other aspires to economic progress (to no longer be "unfortunate"). Both visions are equally legitimate and, in essence, have nothing to do with more or fewer renewables. A sign that the diversity of the Galician rural world (and of society in general) does not fit into a hundred films (or a hundred blog posts).

Unfortunately, climate action is increasingly forcing us to make choices and, not infrequently, to accept that the urgency of decarbonisation requires us to take on one impact in order to avoid a greater one later on. This is no excuse, however, for ignoring the fact that biodiversity loss is another major crisis alongside the climate crisis, so that the (necessary) acceleration of climate action also entails risks if efficiency is not prioritised and if regulation and supervision reduce its effectiveness.

It is thus undeniable that all voices deserve to be heard and heeded. That is why I welcome the fact that films make us reflect and ask questions. I think that a good resolution for this year (and beyond) is to continue supporting culture, so that it continues to raise dilemmas and give a voice to the voiceless.

Jaime Menéndez

Jaime joined the Institute as a Predoctoral Researcher at the Energy Lab in 2015. He has worked on the following projects: “Energy and Industrial Transition” and “Technology, Transport and Efficiency”.