In the beginning of 90s the focus moved to regions and industrial agglomerations (mostly clusters – areas with spatial proximity of companies and other institutions from the same and related industries) as motors of national competitiveness (Porter 1998). Economic gains created within these clusters are able to spillover to the whole region and herewith increase its general welfare. Soon clustering had established a new and complementary methodological way of interpreting and analyzing the advantages of the economy, organizing economic development and constructing effective public policy for enhancing regional competitiveness. Today, when the concept is being applied as an analytical tool or when measures are being developed to stimulate clustering formations – it is considered as cluster policy. Independently of the type and instrument applied, the realization of the effective cluster policy has to be targeted at the engagement and collaboration of three core actors: government, firms and research institutions, named as a “triple helix” (Europe INNOVA 2008, p. 31). Etzkowitz (2002) was the first to use the triple helix model as an instrument for innovation. The actors are similarly equal, independent and overlapping. The existence of this trilateral cooperation particularly ensures “self-reinforcing dynamic of knowledge-based economic development” (Etzkowitz 2002, p.12) of the territory. Later on the model has been extended first to “quadruple” through adding the influence of the civil society and later to “quintuple” helixes by summing the natural environment (Carayannis, Campbell, D. F. J. 2012, pp. 14, 18). The computability of civil society, which is also known as the third sector, is especially essential for the stimulation of clustering processes within the innovation system. The study of the actors´ inter-relations is now building the modest part of the current research. Non-government organizations (NGOs), especially international ones, are one of the elements of the civil society, which haven´t been observed broadly. According to Willetts (2014) an NGO is:

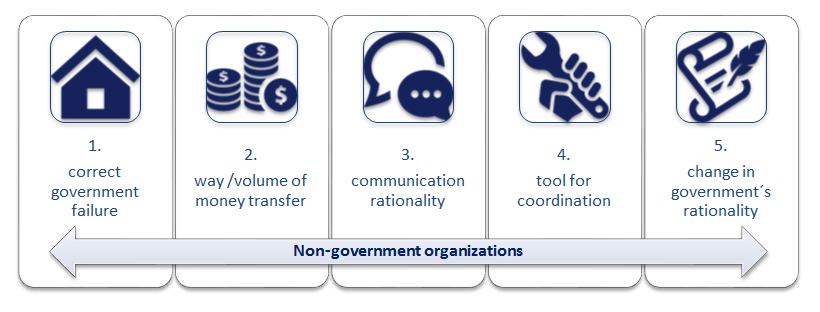

Throughout the last decades the number and behavior of these organizations has strongly increased within the (global) governance. It has happened mainly due to following reasons: 1) difficulty in solving particular issues locally (e.g. poverty, terrorism, environmental changes) , 2) economic liberalization and opening of national barriers in other areas, 3) desire for common peace, security and stability. Herewith, it seems interesting to question its role in the cluster policy, especially within developing and transition countries, which was first brought up in our paper presented at the DAAD-CINTEUS-Workshop in Fulda. From the governance system perspective (OECD 2014) NGOs are recognized as non-state actors. According to Börzel and Risse´s (2010) point of view, governance is a build-up of structure and process. Herewith NGOs are an element of competition or a negotiation system belonging to the structural part of the governance. NGOs can represent different areas of social, economic and environmental aspects. NGOs can be divided into different levels: local, national and international. On the international level, behind international government organizations (IGOs), international NGOs form the second type of actors. The roots of NGO´s birth go back to the establishment of the United Nations. They act based on the same principles as local or national NGOs, thus they are considered to have a broader area of influence, types of members and donors. The activity areas of international NGOs are as broad as the national or regional ones and refer to such aspects as humanitarian functions, citizen concerns for governments, advocate and monitor policies and political participation through provision of information. They provide analysis and expertise, serve as early warning mechanisms and help monitor and implement international agreements. Based on the following five theoretical argumentations we claim that inclusion and participation of NGOs is generally important, especially for the enhancement of cluster policies in developing and transitional countries.

1. Possibility to correct government failure or reduce areas of limited statehood in developing countries.

During the second half of the 20th century, international organizations have noticed that despite the provision of financial support for the states, the level of poverty or economic growth hasn’t significantly improved in these countries. At the roots of this non-success were numerous governmental failures in developing and transition states, which were seen in their inability to develop appropriate policies and mange financial resources. Here the reference can be made to the concept of Börzel and Risse (2010, pp. 118–119), where such failures are called “areas of limited statehood”, reflecting “territorial or functional spaces within otherwise functioning states that have lost their ability to govern”. In the search for new instruments to enhance economic growth in developing countries, institutions such as non-government organizations have proved to be effective. The main reason being that they, like that of the state, are able to create so-called “shadow of hierarchy” (form of environment for negotiations among different actors, where the state can “threaten – explicitly or implicitly – to impose binding rules of law on private actors in order to change their cost-benefit calculations in favor of voluntary agreement closer to the common good rather than to particularistic self-interest” (Börzel, Risse 2010, p. 116)). The areas of limited statehood or government failure negatively affect this environment. External actors, such as international organization or foreign governments, are capable of enhancing the level of governance (Börzel, Risse 2010, p. 122). This same point is also supported by Finnemore and Goldstein (2010). They can do it directly through getting the monopoly over the mechanism of governance or indirectly through the legal right to intervene, due to emerging international norms of “responsibility to protect” (Börzel, Risse 2010, p. 128). In our case the reference can be made to international NGOs, where interference is important due to the ability to support the governance of the government, in case of “areas of limited statehood”.

2. Present additional manners and volume in transferring money from one institution to another.

Developing and transition states often do not to have enough financial resources for the conduction of political reforms. Credit lending from other states or international financial institutions is one of the ways to cover this money shortage. Thus, this kind of funding extends the budget debt and low productivity growth of the economy can lead to a reduction of state credibility. NGOs are also able to develop various programmes and policies, which either are self-sufficient or can be offered to the local or national governments for later implementation. As non-profit organizations, in order to do so they require certain level of funding, which can be offered by different foreign institutions. Herewith, international NGOs can be considered as one of the additional sources for provision of money, the amount being higher than that of national ones, due to the international level of its stakeholders.

3. Communication rationality of the third sector.

NGOs belong to a third sector, which based on the opinion of Mary Kaldor (Corry 2010) can be viewed not as a sector but rather as a process of interaction or communication between different sectors. Based on this opinion these organizations are able to see the world, not according to the “market logic of investment for-profit or a hierarchical logic of formal super- and sub-ordination, but in their ability to transgress such logics and provide identities and action possibilities while closing off others” (Corry 2010, p. 16) The third sector creates dialogue or struggle between different agents, which in other cases would operate according to mutually incomprehensible logics. Herewith, in reference to communicative rationality, NGOs are able to deliberate the process and stand forward as a force of a better argument (Corry 2010).

4. Viewing NGOs as a coordination tool that orders society.

Based on the opinion of Foucault (1978) in Corry (2010) the third sector is a part of the “governmentality” concept, which is seen as a connected system of discourse and techniques or institutions, where some practices flourish and others appear wrong, or just ludicrous. So within this vision NGOs are being used as a tool for making some aspects possible. This notion is particularly supported in liberal western orders (Corry 2010).

5. Change in the rationality of the government itself.

Sending and Neumann (2006) think that non-state actors have a subject role in shaping and carrying out global governance-functions and that this wasn’t caused due to the transfer of power from the state. The reason that NGOs appeared as actors is due to the general transformation of its conceptionalisation from the object to the subject perspective in the system of governance. Sending and Neumann (2006) stress that this change is not due to the reduction of the state power or its sharing, but that it was always there and has now been reconsidered. Based on the before mentioned argumentations, the importance of NGOs in the process of policy making, especially as an assistant to government, seems to be very evident. While drawing conclusions it is worth reminding that in the enhancement of clustering processes at least the engagement of three key actors has to be secured. Thus our argument is that in developing and transitional states, where the biggest problems are the existence of an ineffective government and limited financial resources, the participation or involvement of NGOs, especially international ones, can play an additional contributing role leading to the effective realization of cluster policy. Mainly, as they are not only fulfilling their role in the quintuple helix, but also overtake the tasks of the government. This opinion opens additional lines for further research, which can be studied in cluster cases not only in developing and transitional countries, but also in the comparison of industrial ones.

Egile honen artikulu gehiago

-

2016-09-26

Learning from others: Malopolska región winner of the European Entrepreneurial Region 2016 award -

2016-05-18

Culture and economic development, what is the link? Three examples from the Basque Country -

2016-02-02

From silver to gold…Ingredients for the next years of the successful Basque cluster policy -

2013-05-19

Supporting cross-border inter-clustering, why matter? -

2012-12-12

Creating innovation – “talent” or a skilled team?