One cannot understand the rise of populism without the decline of industrial regions that have experienced prolonged economic decline. As Rodriguez-Pose (2018) explains, on the basis of these, as well as other peripheral or economically lagging regions, a geography of discontent has been consolidated in which their inhabitants have felt systematically ignored by economic and development policies.

Donald Trump has consistently championed the idea of bringing manufacturing back to the United States as one of his economic and political priorities since his 2016 campaign, channeling resentment toward globalization from many communities that suffered disinvestment, factory closures, and loss of good-paying jobs. His talk of “bringing jobs back” and “making America great again” especially resonated with non-college-educated white workers, a group that represents a significant portion of his voters. During “Liberation Day” he appeared accompanied by workers from industrial sectors such as automotive, steel and agriculture; a few days later he appeared signing executive orders aimed at boosting the coal industry with some miners. This whole “blue collar” universe that tries to revive American industrial pride evokes in me movies set in the 60s and 70s, such as The Huntsman, and a question arises in my mind: what is the manufacturing imaginary that Trump has in mind?

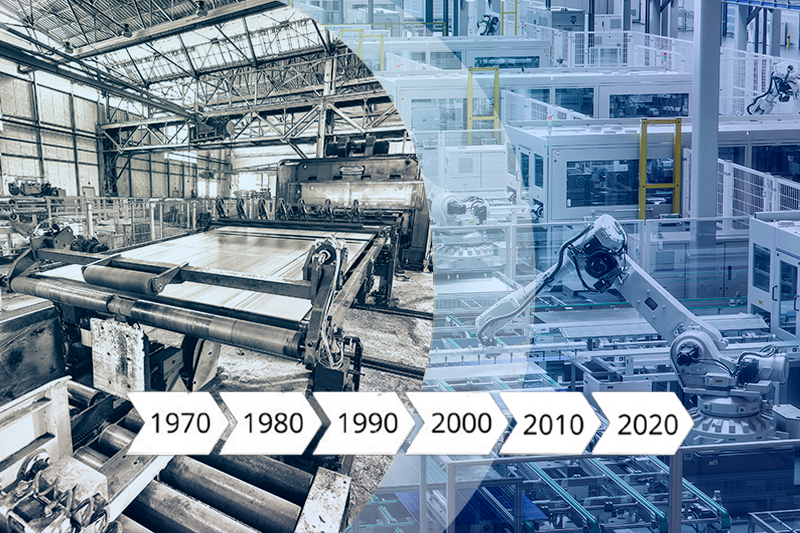

The manufacturing of 2025 cannot be equated with that of 1979, the year when this sector reached its all-time high in U.S. employment, with nearly 19.6 million workers. At that time, large factories were predominant, heirs of the Fordist model, very different from today's manufacturing, where automation is inexorably transforming production processes. The future is moving towards connected smart factories and plants, even in different countries, where supplies, logistics and production are synchronized and, through sensor technology, all variations in machines, robots and assembly lines are monitored and captured. Smart factories can reconfigure their processes quickly to respond to changes in demand or customize production and, because they are robotized, require little or no direct human intervention. China has the third highest robot density in the manufacturing sector in the world, reaching 470 units per 10,000 employees, behind only South Korea and Singapore. The USA ranks 11th, with 295, about 40 % less.

There is a second differentiating factor. The profile of workers in demand in this manufacturing paradigm differs substantially from that which prevailed in the 1970s. They have higher technical qualifications and a holistic view of the production process; it is no longer enough to know how to operate a machine; they need to understand how the automated system as a whole works, interpret data and collaborate with digital tools. Workers are also required to have a great capacity for adaptation and problem solving in an environment where lifelong learning is essential. This is the trend that is taking hold.

This change highlights the critical role played by both vocational and university training in the generation of these profiles, as well as in the capacity of the training system to quickly retrain workers. It is likely that many operators in smart factories, due to their level of qualification and their work disposition (in an environment in which the most rigid Fordist production processes have lost their meaning), are more similar to a white collar than to a 1970s blue collar. In the case of the United States, this transformation is no small matter: as J. D. Vance points out in his book Hillbilly Elegy, part of the abandoned white working class feels distrustful of the educational system, which they no longer perceive as a guarantee of progress.

This brings us back to the initial question: can manufacturing activity be part of the solution for the abandoned communities to recover the position they have lost? Is it enough to attract investment and reopen factories, or is it necessary to act in other areas as well? It is true that, since the 2008 crisis, industrial employment has established itself as more stable and with better working conditions than much of service sector employment. However, to achieve that ideal, it is essential to link industry to the training fabric and adapt it to a new digital and sustainable production paradigm that requires, among other things, increasing levels of qualification. It is also very likely that robotization, machine learning and other emerging technologies will tend to reduce the demand for labor in the manufacturing sector. This calls for the promotion of strong career paths in other economic sectors that may have deteriorated in recent years. For all these reasons, in the short term and in this scenario, the message of recovering manufacturing seems more an exercise in nostalgia, possibly deliberate, than a viable project for the modernization of the country.

Finally, the regeneration of neglected territories and communities requires not only the diversification of employment opportunities, but also the active promotion of decent and affordable living conditions, as well as the restoration of people's trust in institutions.

Mikel Albizu

Mikel Albizu is a research technician at Orkestra. At present he combines his doctoral studies with the participation in several research projects.

His main research area is employment and the factors that drive it at a regional and local level, although he has also studied and worked in the field of urban planning and territorial planning.